What does it mean to disappear? It's a cold night and I am shivering outside the Café de Paris in London. I'm standing behind Trevor, hoping that his TV producer status will get me in, when Karen Binns, doorkeeper to this hippest of '90s dance nights, lets me through. It's over for you, she laughs, which in her Brooklyn back-to-front street talk, means it's happening for me. As it turns out it was prophetic both ways. Because the last time I saw her was at a family gathering a year later, as I was about to leave the city.

It's two minutes to twelve, she said.

What does any of this have to do with extinction you might ask? Bear with me. To know how to deal with disappearance, you have to know about your own. To know that when you go, there is a world of difference between being ignored and being seen.

For a few weeks now. I've been wondering what to write about extinction. Does the world need another elegant essay on nature in peril, another rant about palm oil deforestation? Is there a way to look at the disappearance of species without descending into melancholy and apocalyptic data? Could I get that annoying wistfulness out of my voice, avoid the righteous tragic tone of the activist, or repeat the litany of scientific facts about ecological catastrophe which you and I already know?

|

| The Witch of St Kilda by Kaite Tume, embroidery on linen from 'Extinct Icons and Ritual Burials' (Issue 13) |

Loss of species is one of the key strands within the work of Dark Mountain: from Nick Hunt's story Loss Soup (in Issue 1) to Michael Cipra's Who Cries for the Archduke? (in Issue 13), from Feral Theatre's performance about the Tasmanian tiger to Andreas Kornwall's 'Life Cairn for Lost Species'. But perhaps its most significant act has been the curation of a space in which writers and artists, readers and participants can communicate this collapse without fighting their corner: we all know something is going down. That the clock stands before midnight.

That if a vanishing is required it is our civilisation's story of human centrality.

|

| 'Extinction Cabinet' by Nicholas Kahn & Richard Selesnick. From ‘Truppe Fledermaus: 100 Stories of the Drowning World' (Issue 9) |

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN THE CRYING STOPS?

You are supposed to feel grief, but grief is not what I feel when I hear a chainsaw outside, or read about Icelandic fishermen killing a blue whale. I do not mourn non-violently when I hear about the Chinese trading jaguar teeth, rhino horns and pangolin scales, or the British slaughtering mountain hares and golden eagles (in order to slaughter more grouse), or Maltese and Cypriot hunters killing millions of migrating songbirds - all those men with knives and guns and axes proving their 'masculinity' (and the women who stand by them and beget their children). In spite of knowing better, I find myself shouting, It's over for you! - and not in the way Karen Binns once meant it.When the fury subsides, or I return home having argued with the tree cutters, what is left is a retraction, a lessening in the core of my self, countered by a refusal to feel dispirited, or to fuel the darkness of our civilisation, to let the Empire take my heart. But I do not grieve. Grief takes you inward to your own bereavement, to project the loss of small edens or family upon a beleaguered Earth. There is a power in grief, as all writers, particularly those who write about nature, know (where would Helen Macdonald's H is for Hawk have been without her dead father, or Robert Macfarlane's Wild Places without Roger Deakin?). Absence has as strong a pull as presence. Your capacity to see straight and communicate directly with the non-human world however is impaired. Our great sorrow is not what the Earth wants from us, any more than a dying person ever wants our tears. They want you to show it mattered they were here. It's not about us after all. Human beings are not becoming extinct.

|

| Remembrance Day for Lost Species; Memorial to the Passenger Pigeon by Emily Laurens, Photo Keely Clark: (Issue 7) |

I see I am left with a nervousness, a nervousness that senses the decline in some part of the web, a weakening in the links between insect and bird, plankton and fish, between plant and the human imagination. And so I act in whatever way I can to bridge the gap: I put my hand on the severed trunk of the tree; I carry the dead otter from the road and bury her in the marsh; I write in defence of the feeding grounds for the red-listed curlew on neighbouring AONB farmland now threatened with extraction. But most of all I try to find out how to shift our logger-headed perception, our ways of seeing and imagining the world from where we all stand, seemingly stuck in a parasitic culture that refuses to become symbiotic.

In many ways artists fulfil the function of the old medicine people and storytellers: they keep the bridge open to the living Earth and show how we can give back to a planet that has given us everything we know. Their act is to see and not falter, to reflect what is happening and speak to those inchoate places inside us. It is not an easy position to hold, because destruction is not easy to watch. But through their work we can look without turning away, because they themselves faced the disappearance and did not escape in their minds, or give in to rage or powerlessness. They bore witness and let the walls that separate us from the fate of the planet fall down inside them.

We follow their track.

HOLDING THE BASE LINE

When the world shifts and we don't notice, something happens: we move away from what is known as the ancestral or original instruction, our way of keeping the Earth intact. We don't notice that hills that were once forested become bare scrubland, or that it's become normal to see a handful of butterflies when only a decade ago there were hundreds. The writer, George Monbiot's response to this 'shifting baseline syndrome' in his book Feral was to imagine a reinvigorated Earth and foster a culture of rewilding, the restoration of territories in which wild animals and plants could thrive again and flourish.So what if, instead of drifting with the tide, we resist it? What happens if we remember how it was at one time and refuse to forget? That we hold what is and was dear in our neighbourhoods in connection with the forests and oceans everywhere?

David Ellingsen is a Canadian artist whose photographic work centres on the loss of the natural world and the reintegration of the 'intricate relationships between land, ocean, flora, fauna and atmosphere ... back into our technological, urbanised culture'. His sharp graphic eye ranges from observing the changing sky over a year, to the body of an orca cut up on the British Columbian shore. to a juxtapostion of a human skull filled with the skulls of other creatures. 'At The Edge of the Answer No 2' (see above) was the opening image in our latest issue TERRA, from his series Solastagia.

The Last Stand by David Ellingsen

|

| Installation 3, Lance-tooth Crosscut Saw by David Ellingsen. Western Red Cedar, Pigment ink on cotton rag |

'This project, The Last Stand, was photographed on my family’s land here in Canada – in fact it was my great grandfather and great uncle who cut down these very trees over 80 years ago. The vast old growth forests of British Columbia have mostly vanished, with only 1% remaining, a situation reflected in the great forests around the globe. Disappearance and loss are a consistent theme running through my work and I remain compelled by an unrelenting, creative urgency as the ecological crisis deepens. In fact, after decades of warning from our civilisations’ brightest minds, I feel it my duty to do so.

It is my hope that creative work which encourages emotional connection with the issues and engagement with the grieving process (that rightfully accompanies this diminishment of life) will help us move through the seemingly ‘frozen’ state our civilisation is in and into a period of rapid acceptance and mobilisation to repair what we still can.' DE

SEEING THOUGH THE DARK GLASS

There is a point at which you get 'woke'. It is a terrifying moment, as the cocooned world you knew cracks open. But it is also a moment of kinship - not only with our fellow creatures, but with our ancestors who left depictions of this relationship on the walls of Neolithic caves, or shards of ancient Pueblo pottery.The current intellectual discussion about ecosystems and carbon emissions speaks to our rational minds but does not connect with our physical, kinetic intelligence, our creaturehood, the places where we feel kin with the rest of life. For that we need physical encounter in order to engage and act.

The sculptor Stephen Melton brings a visceral attention to the fate of the natural world at our hands: to native sharks mutilated for their fins (see above in 'Thanet Fish') to the illegal pet trade to the destruction of the Indonesian rainforest, with carved and often entwined and adorned figures of animals, birds and fish.

Dreamland by Stephen Melton

|

| Dreamland by Stephen Melton. Work in progress that contains the forms of lost or disappeared creatures including orangutans, hedgehog, killer whale, rhino, cane toad, polar bear, sperm whale, tiger, sea turtles, coral, giant anteater, orange bellied parrot, carrier pigeon, pangolin and moths, Below: detail with bat. |

'We live in such a visual world today; a world in which we are bombarded by images through digital and social media. Often, if the image hasn’t been constructed using the "click-bait" brief, it is often overlooked.

Sometimes I choose to work with an aesthetic that is beautiful, familiar and fun, which can be seen in my current work in progress ‘Dreamland’ – an intricately cast carousel in bronze. However, I then subvert the aesthetic by presenting my concerns about social behaviour and our attitudes towards our natural world.

I hope that using beauty to attract the audience will then engage them in the visual paradox the work presents. Using global fonts, the headlines of our most prominent socio-ecological problems today adorn the whole structure, in a similar manner of the carousels of the past. Hand-carved and subsequently cast skeletons of animals weave around the attraction, in an ominous manner. Each species has been chosen because of their current fragile existence due to humanity's impact on the world.

Like sheep, many of us follow unquestionably patterns of human behaviour without any understanding of the consequences, repeating mistakes of our past. A decaying ride that we are unable to alight.' SM

HONOURING

In 2001, the UK filmmaker Nick Brandt went to Kenya and began a photographic odyssey: to capture on film the disappearing great fauna of southern Kenya. The elephants stand as giant billboards in a broken landscape, under a flyover in the 2014 series Inherit The Dust; in This Empty World – his latest book to be released next February – they are juxtaposed amongst the industrial infrastructure, machines and human presence that threaten them on all sides.Elephants (killed at a rate of 100 a day for their ivory), lions, giraffes and hyenas, are all photographed with a medium lens camera, as black and white portraits, closeup, still, without drama, or special effects.

'What I am interested in is showing the animals simply in the state of Being,' he writes in the first of his trilogy of books, On This Earth. 'In the state of Being before they are no longer are. Before, in the wild at least, they cease to exist. This world is under terrible threat, all of it caused by us. To me, every creature, human or non-human, has an equal right to live, and this feeling, this belief that every animal and I are equal, affects me every time I frame an animal in my camera. The photos are my elegy to these beautiful creatures, to this wrenchingly beautiful world that is steadily, tragically vanishing before our eyes.'

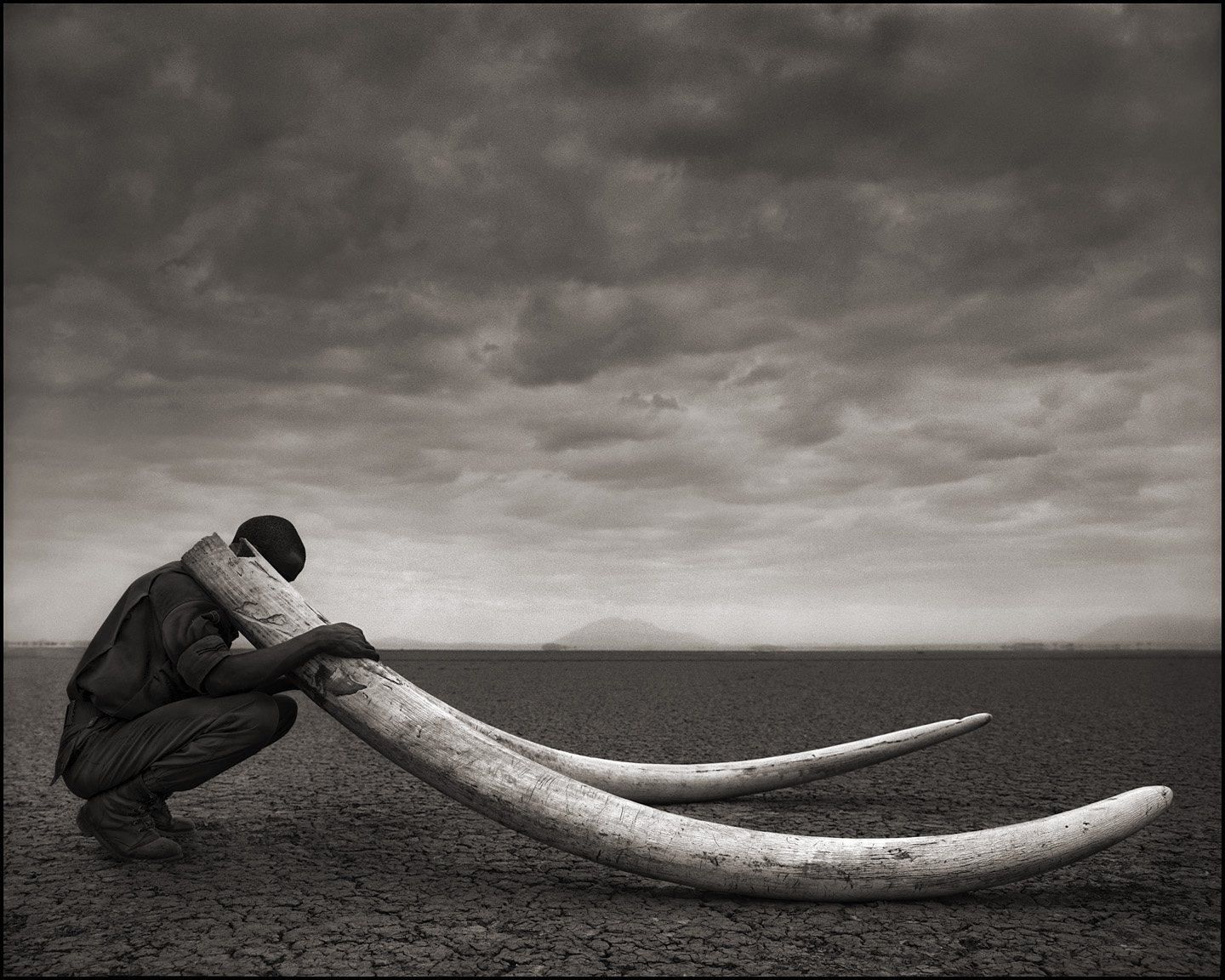

Ranger with Tusks of Elephant Killed at the Hands of Man by Nick Brandt

|

Ranger with Tusks of Elephant Killed at the Hands of Man, Ambrosselli, 2011 by Nick Brandt |

The elephant was killed by poachers in Tsavo in southern Kenya in 2004. His tusks were stored in Kenya Wildlife Service’s ivory strongroom. In July 2011, they permitted me to borrow these and many other tusks of killed elephants for the ranger series.

This photo features one of 200 rangers employed by Big Life Foundation, the nonprofit organisation that I co-founded with conservationist Richard Bonham in 2010 to help protect and preserve the wild animals of a critically important 1.6m acre area of East Africa.

Photographed on medium format black and white film, I waited several days for the normal clear blue skies to disappear, waiting for the right sombre cloud cover to take the photos.' NB

ALLEGIANCE

One of the main reasons people don't want to see, to wake up, is to feel the emptiness that the violence of civilisation leaves behind. We live in a world that promises freedom from suffering with its tinsel politics and cheap distractions. But you never get a relationship with the living Earth that way, the feeling that you are connected. The relationship with the Earth - whichever way you learn to love it - through a land, creature, plant, or ocean - is a relationship that never falters and will never, unlike civilisation, let you down.However, there is a bargain you make when you forge that relationship, an ancient bargain human beings have made over millennia. Our allegiance goes both ways.

Dark Mountain Issue 7 featured Silent Spring by Chris Jordan and Rebecca Clark (detail above, see full picture here) which depicts 183,000 birds, the estimated number of birds that die in the United States every day from exposure to agricultural pesticides. It forms part of his series Running the Numbers: An American Self-Portrait which looks at consumer culture through the austere lens of statistics. However, the photographer is most well known for his close-up portraits of dead albatross chicks on the remote island of Midway in the Pacific Ocean, their stomachs full of discarded plastic.

The recent documentary about his experiences is a searing gaze at the extraordinary beauty of a bird and its fate as it encounters the debris of our fossil-fuelled world.

Albatross by Chris Jordan

Chris Jordan's ALBATROSS film trailer from chris jordan photographic arts on Vimeo.

'The biologists here are finding that the birds all have plastic inside them. Each time I opened one up was like a gallery of horrors. But I believe in facing the dark realities of our time, summoning the courage to not turn away. Not as an exercise in pain, or punishment, or to make us feel bad about ourselves, but because in this act of witnessing a door opens.

'The most difficult thing to bear, for me, was what I knew but they couldn't know about why they were dying. In this experience, the true nature of grief revealed itself. I saw that grief is not the same as sadness or despair. Grief is the same as love. Grief is a felt experience of love for something we're losing, or have lost. When we surrender to grief it carries us down to our deepest connection with life.

I didn't know I could care about an albatross.' CJ

.jpg)

Dark Mountain: Issue 20 - ABYSS is available

Dark Mountain: Issue 20 - ABYSS is available